Super-Earths, Sub-Neptunes, and Transitional Exoplanets

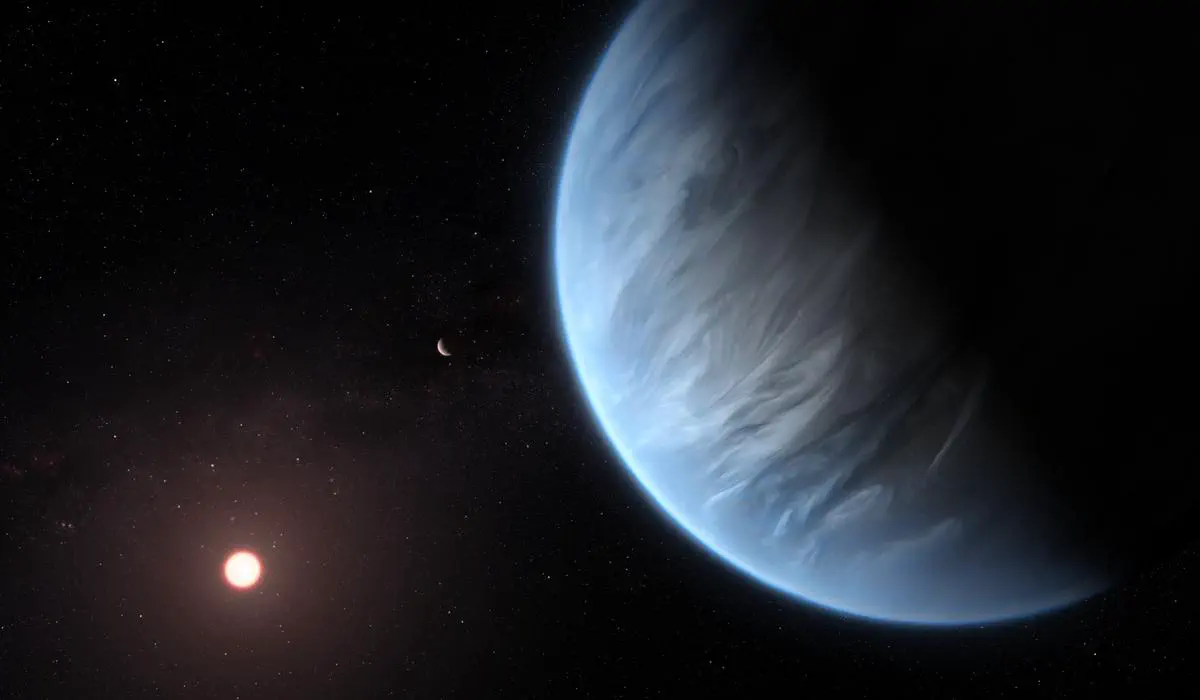

Image Credits: ESA/Hubble, M. Kornmesser

Image Credits: ESA/Hubble, M. KornmesserTransitional exoplanets are planets that occupy the intermediate range between the well-defined classes that are Super-Earths and Sub-Neptunes. Super-Earths are rocky planets, while Sub-Neptunes are gaseous planets with hydrogen-rich atmospheres. Transitional planets are of unknown composition: they typically fall in the size range of about 1.5 to 3 Earth radii, where the distinction between rocky planets and gas-enveloped planets becomes blurred. They are of particular interest because they may represent evolutionary stages between terrestrial and gas-rich planets - a key regime to understanding how planetary atmospheres form, evolve, and sometimes dissipate over time.

One of the major challenges in studying small exoplanets lies in accurately determining their composition and internal structure: are they mainly rocky, gaseous, or even full of ice and water? Radius and mass measurements alone cannot definitively reveal whether such a planet is a dense rocky core with a thin gaseous envelope, or a volatile-rich body with a significant hydrogen-helium atmosphere. At ExoAIM, we study the atmospheres of these small exoplanets using spectra from JWST to determine their composition. This adds a third constraint that can help up differenciate these worlds.

This small planet regime is difficult. It is compounded by observational uncertainties: current instruments often have limited precision in measuring small variations in planetary mass and radius, especially for faint host stars. As a result, even small errors can drastically alter interpretations of a planet’s bulk composition. We therefore work on understanding instrumental systematics as best as possible to ensure robust interpretation.

Stellar activity — such as flares and spots — also enters the equation: these effects can contaminate transit spectra, masking or mimicking atmospheric signals; especially as most of these small planets are studied around active M-type stars. We are therefore interested in studying the host stars and developing techniques to account for contamination effects. Additionally, the intermediate temperatures of these planets often mean that condensates and aerosols form in their atmospheres, flattening out spectral features and complicating retrievals of molecular abundances.

Studying these transitional planets is challenging, but crutial to the advancement of our planetary understanding. Existing planet formation and evolution models struggle to explain the observed “radius valley” — a gap in the distribution of exoplanet sizes that separates super-Earths and mini-Neptunes - and the “Sub-Neptune desert” - a statistical lack of short orbit Sub-Neptune size exoplanets. Competing hypotheses, such as photoevaporation driven by stellar radiation and core-powered mass loss, each predict different evolutionary pathways for transitional planets and different atmospheric compositions. Disentangling these processes requires to study the atmospheres of many of these planets across a wide range of planetary ages and stellar environments.